The Kurdish word “Peshmerga” translates as “one who faces death” – it’s also the name of Iraqi Kurdistan’s military force. After the so-called Islamic State or ISIS militants attacked Iraqi Kurdistan, drastically changing the autonomous region’s stability in 2014, the Peshmerga have played a major role in defending Kurds, Arabs and refugees alike. Peshmerga soldiers, some as young as 17, fight ISIS with very little supplies often using archaic, Russian-made weapon systems dating from the 1950’s. A soldier will typically make about $300 USD a month - many of them send their earnings home to support their wives and children. Because of a lack of funding from the government they most often buy their rifles with their own money on the black market, while many of them use their own vehicles in the conflict, driving their personal cars to the front line or riding in the flat bed of unarmored trucks. Since the battlefield often leaves no time for sleeping, soldiers take short naps during the day in between heavy episodes of fighting. Regarding his units’ shortage of body armor and helmets due to a lack of funding, one soldier stated, “This is war. If God wills us to die in war, we will die. Body armor won’t stop that.”

An Assyrian Christian woman shows her cross necklace at a Christian revival in Dohuk, Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

The Nineveh Plains in Northern Iraqi Kurdistan serve as home to some of the oldest continuous religious communities in the world, including the Assyrians and the Yezidis, who are indigenous to the region. In 2014 when ISIS or the so-called Islamic State began moving across the province targeting and persecuting Yezidis, Assyrian Christians, and the region’s other minority groups, many locals retaliated by forming small militant rebel factions, such as the Christian Dwekh Nawsha militia, the NPU (Nineveh Plain Protection Units), and the Yezidi YBS, or Sinjar Protection Units (an offshoot of Syria’s YPG). Parts of Northern Iraq now remain a battleground where religion, faith, hostility, violence and infighting over territory collide on ancient land.

Flowers and radios adorn the walls at a Dwekh Nawsha military base near Baqofah, Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

An NPU militia soldier shaves, looks at his phone and smokes a cigarette at an NPU military base near Sharafiyah, Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

A Christmas tree at St. George's Chaldean church in the village of Baqofah, which was abandoned after it was attacked by ISIS militants. Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

Dwekh Nawsha soldier Marcus Nissan jokes around with a fellow soldier while driving to their unit's base in Baqofa, Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

Sundis Ziad Hassan wears a white gown, a Yezidi tradition, as she walks to pray at the Lalish temple, the most sacred and only Yezidi temple in the world, Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

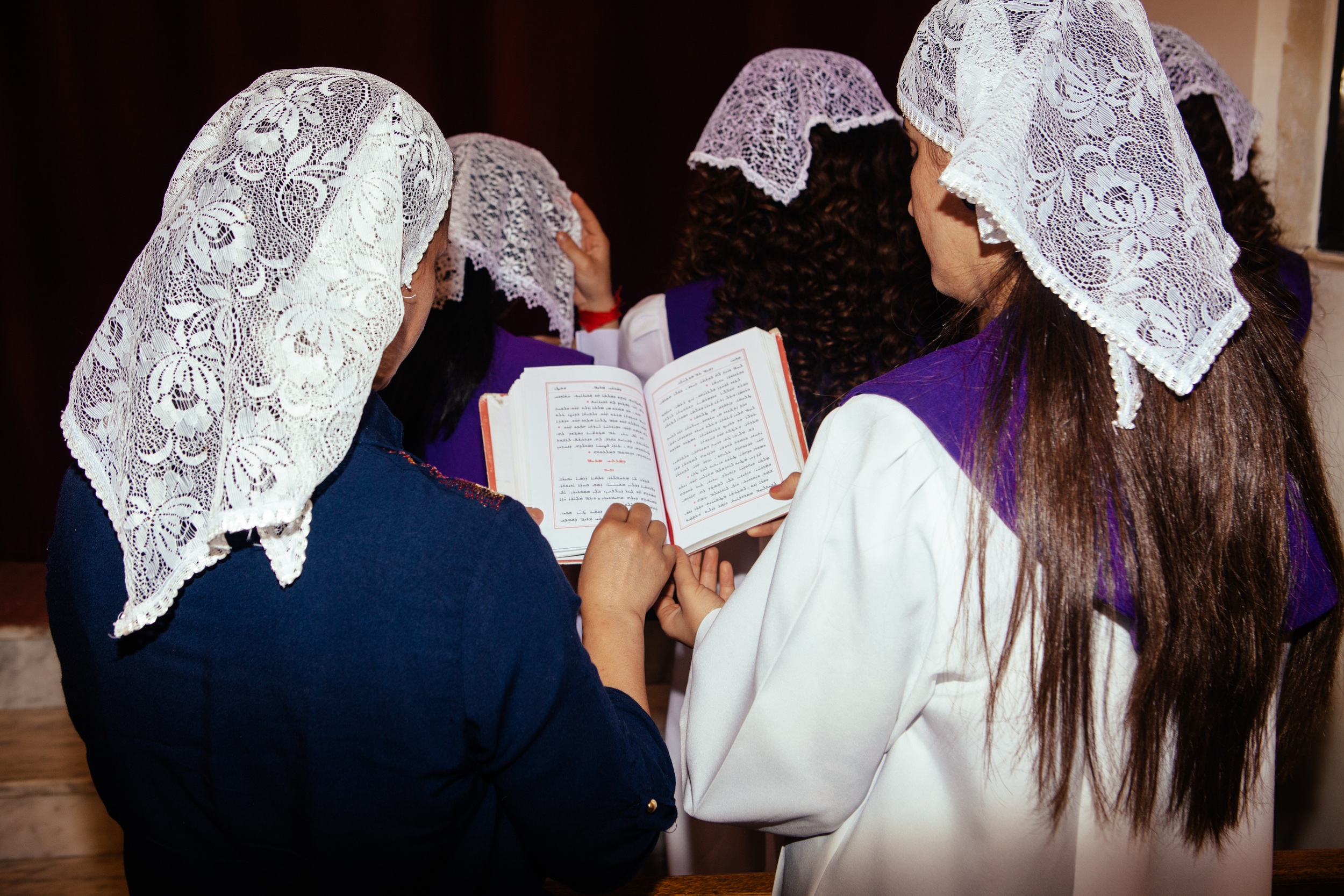

A woman attends mass at a Catholic Church in Dohuk, Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

Children participate in a religious Yezidi ritual by kissing holy scarves as way to make a wish in a temple at Lalish, the most sacred and only Yezidi temple in the world, in Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

Girls carry food and other items down a staircase at Lalish, the most sacred and only Yezidi temple in the world, in Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

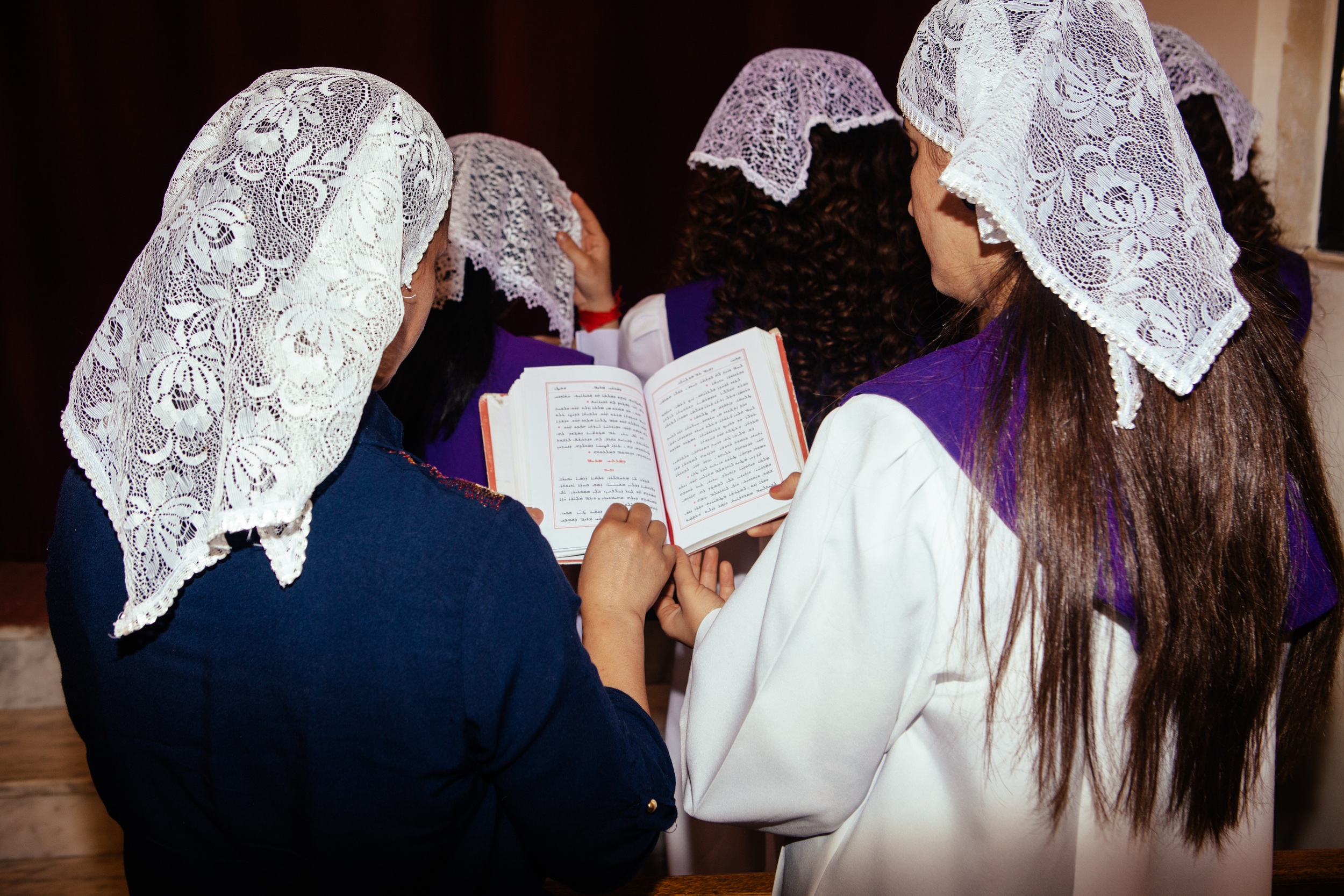

Girls sing in a choir during Catholic mass at church in Dohuk, Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

A bird flies out of Lalish temple which features a stone black snake on it's wall in Northern Iraqi Kurdistan. Lalish is the most sacred and only Yezidi temple in the world. According to legend, the snake was once a live serpent but was transformed it into a solid fixture by Sheikh Adi when it attempted to scale the wall of the temple.

Two birds fly in a room adorned with crosses at St. George's Chaldean church in the village of Baqofah, Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

A statue of Mary and the Christ child is covered in plastic bubble wrap in the convent of St. George's Chaldean church in the village of Baqofah, Northern Iraqi Kurdistan. The convent was ransacked and looted by either ISIS militants or Peshmerga soldiers which damaged many of the church's religious icons.

The Kurdish word “Peshmerga” translates as “one who faces death” – it’s also the name of Iraqi Kurdistan’s military force. After the so-called Islamic State or ISIS militants attacked Iraqi Kurdistan, drastically changing the autonomous region’s stability in 2014, the Peshmerga have played a major role in defending Kurds, Arabs and refugees alike. Peshmerga soldiers, some as young as 17, fight ISIS with very little supplies often using archaic, Russian-made weapon systems dating from the 1950’s. A soldier will typically make about $300 USD a month - many of them send their earnings home to support their wives and children. Because of a lack of funding from the government they most often buy their rifles with their own money on the black market, while many of them use their own vehicles in the conflict, driving their personal cars to the front line or riding in the flat bed of unarmored trucks. Since the battlefield often leaves no time for sleeping, soldiers take short naps during the day in between heavy episodes of fighting. Regarding his units’ shortage of body armor and helmets due to a lack of funding, one soldier stated, “This is war. If God wills us to die in war, we will die. Body armor won’t stop that.”

An Assyrian Christian woman shows her cross necklace at a Christian revival in Dohuk, Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

The Nineveh Plains in Northern Iraqi Kurdistan serve as home to some of the oldest continuous religious communities in the world, including the Assyrians and the Yezidis, who are indigenous to the region. In 2014 when ISIS or the so-called Islamic State began moving across the province targeting and persecuting Yezidis, Assyrian Christians, and the region’s other minority groups, many locals retaliated by forming small militant rebel factions, such as the Christian Dwekh Nawsha militia, the NPU (Nineveh Plain Protection Units), and the Yezidi YBS, or Sinjar Protection Units (an offshoot of Syria’s YPG). Parts of Northern Iraq now remain a battleground where religion, faith, hostility, violence and infighting over territory collide on ancient land.

Flowers and radios adorn the walls at a Dwekh Nawsha military base near Baqofah, Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

An NPU militia soldier shaves, looks at his phone and smokes a cigarette at an NPU military base near Sharafiyah, Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

A Christmas tree at St. George's Chaldean church in the village of Baqofah, which was abandoned after it was attacked by ISIS militants. Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

Dwekh Nawsha soldier Marcus Nissan jokes around with a fellow soldier while driving to their unit's base in Baqofa, Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

Sundis Ziad Hassan wears a white gown, a Yezidi tradition, as she walks to pray at the Lalish temple, the most sacred and only Yezidi temple in the world, Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

A woman attends mass at a Catholic Church in Dohuk, Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

Children participate in a religious Yezidi ritual by kissing holy scarves as way to make a wish in a temple at Lalish, the most sacred and only Yezidi temple in the world, in Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

Girls carry food and other items down a staircase at Lalish, the most sacred and only Yezidi temple in the world, in Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

Girls sing in a choir during Catholic mass at church in Dohuk, Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

A bird flies out of Lalish temple which features a stone black snake on it's wall in Northern Iraqi Kurdistan. Lalish is the most sacred and only Yezidi temple in the world. According to legend, the snake was once a live serpent but was transformed it into a solid fixture by Sheikh Adi when it attempted to scale the wall of the temple.

Two birds fly in a room adorned with crosses at St. George's Chaldean church in the village of Baqofah, Northern Iraqi Kurdistan.

A statue of Mary and the Christ child is covered in plastic bubble wrap in the convent of St. George's Chaldean church in the village of Baqofah, Northern Iraqi Kurdistan. The convent was ransacked and looted by either ISIS militants or Peshmerga soldiers which damaged many of the church's religious icons.